Evil and Suffering in the World of a Good and Sovereign God

Where is God?

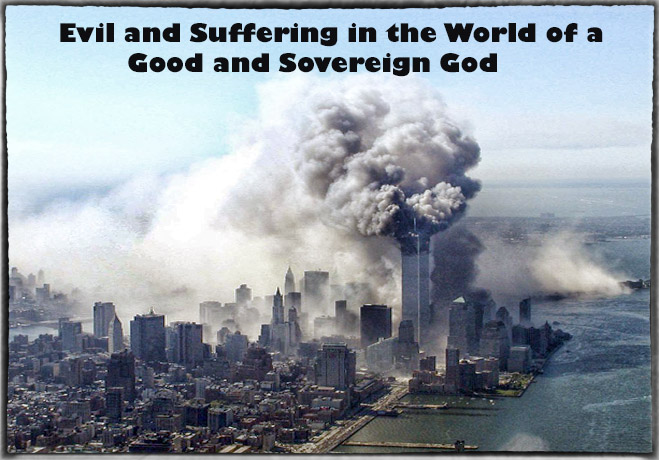

There are highly public catastrophes. Terrorists fly airplanes into the World Trade towers and into the Pentagon. A tsunami of gigantic proportions, caused by shifting plates in the ocean floor off the coast of Aceh in northwest Indonesia, causes horrific damage in several countries, and kills about 300,000 men, women, and children.

The truth of the matter is that all we have to do is live long enough, and we will suffer.

In any and all of these tragedies, in all of this pain, where is God?

2 Cor 4;8 We are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair; 9 Persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed; 10 Always bearing about in the body the dying of the Lord Jesus, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our body.11 For we which live are alway delivered unto death for Jesus’ sake, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our mortal flesh. 12 So then death worketh in us, but life in you.

It’s a reflection of the fact that we no longer believe that the world is under a curse and people will suffer. So that when people do suffer, there are no categories for it.

We expect some suffering in all those nasty areas where people hate each other and have for centuries.

We have not come to terms with the pervasive nature of evil. If we don’t really accept the biblical pronouncements on sin, its universality, the capability of human beings to descend to the gutter, the imperative of social restraint, and then the fact that rotten families, apart from the intervention of the grace of God, produce rotten kids.

You sow the wind, you reap the whirlwind, but you don’t expect that because the social services are meant to take it over. Nobody’s supposed to die. We have National Health. Now for the first time, therefore, this whole century (as opposed to virtually all the centuries in the Western world before that), we do not expect to suffer. We do not expect to die. Whereas, 150 years ago, almost every family lost one or two babies along the line.

So we simply have no categories for evil and suffering, and the result is when it does happen, you blame God. You blame the government. You blame the police. You blame the gun laws, and so on. There’s no doctrine of depravity,

Just because you live in North America or in England doesn’t mean that you don’t get leukemia. People do die. We are under the curse. It’s surprising that anybody is still alive, God have mercy on us. Unless you build that kind of worldview into things, then the first time something bad happens, you have no categories. You have just enough theology to curse God, but not enough theology to find any comfort in him, which is a terrible state to be in.

Humans inhabit a world that has limits.

1John 1:5 This then is the message which we have heard of him, and declare to you, that God is light, and in him is no darkness at all.

What John does is put down a plank that shows Christianity isn’t quite like either of them. “God is light; in him is no darkness at all.” That’s unlike monism. Monism says God embraces good and evil; all that is embraces good and evil. It’s all on the same plane, but that’s not the kind of God we have.

The God of the bible is only good. He is only light. There is no evil in God, and that’s an important truth to get hold of because there are times when Christians face problems of evil and suffering and disease and disappointment and decay,

On the other hand, there is a lot of evil around. That means the question has to be raised …

Why is there evil and suffering in the world?.

Behind that sort of question, the assumption seems to be something like,

“If God is good and all-powerful, then surely he ought to arrange things so that there is no suffering under any circumstances, and everybody should live a happy life.”

Have you experienced serious suffering? How does your experience of suffering (or relative lack of experience with it) affect the way you think about the problem of suffering?

According to the logical version of the problem it’s logically impossible for God and suffering to both exist. If one exists, then the other does not. Since suffering obviously exists, it follows that God does not exist.

The key to this argument is the atheist’s claim that it’s impossible that God and suffering both exist. The atheist is claiming that the following two statements are logically inconsistent:

1. An all-loving, all-powerful God exists.

2. Suffering exists.

3. If God is all-powerful, He can create any world that He wants.

4. If God is all-loving, He prefers a world without suffering.

If God is sovereign, all-knowing, and good, then why is there evil?

The Bible as a whole, and sometimes in specific texts, presupposes or teaches that both of the following propositions are true:

God is absolutely sovereign, but his sovereignty never functions in such a way that human responsibility is curtailed, minimized, or mitigated.

Human beings are morally responsible creatures, they significantly choose, rebel, obey, believe, defy, make decisions, and so forth, and they are rightly held accountable for such actions; but this characteristic never functions so as to make God absolutely contingent.

The view that both of these propositions are true is called compatibilism. the two propositions are taught and are mutually compatible. That both of these propositions are true is based on an inductive reading of countless texts in the Bible itself,

God is absolutely sovereign.

“Why do the nations say, ‘Where is their God?’ Our God is in heaven; he does whatever pleases him” (Ps. 115:2–3).

“The LORD does whatever pleases him, in the heavens and on the earth, in the seas and all their depths” (Ps. 135:6).

Indeed, he is the one who “works out everything in conformity with the purpose of his will” (Eph. 1:11). He not only assigns times and places (Acts 17:26), but so reigns that even the most mundane natural processes are ascribed to his activity. If the birds feed, it is because the Father feeds them (Matt. 6:26);

So certain is Amos of the Lord’s sovereignty even in the military crushing of a city that he can mock the stupidity of those who fail to acknowledge it and learn from it (Amos 3:6). “I am the LORD, and there is no other. I form the light and create darkness, I bring prosperity and create disaster; I, the LORD, do all these things” (Isa. 45:6–7).

At no point is any human relieved of a responsibility, just because God is in some way behind this or that act.

The second proposition is our responsibility

“Now fear the LORD and serve him with all faithfulness … But if serving the LORD seems undesirable to you, then choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve … But as for me and my household, we will serve the LORD” (Josh. 24:14–15).

This is one of only countless passages where human beings are commanded to obey, or where they are entreated to do something, or told to choose or take firm resolution.

The Ten Commandments have bite precisely because they can be obeyed or disobeyed. The gospel call itself lays down profound responsibility: “If you declare with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.

Yet nowhere does such material ever function to make God absolutely contingent, absolutely dependent for his being or choices on the moves taken by human beings.

In no case is human responsibility permitted to function in such a way that God is absolutely frustrated, blocked, and unable to proceed with what he himself had absolutely determined to do.

There is nothing in the Bible quite like those modern writings that argue, for instance, that because men and women make moral choices, therefore God must be limited in power or knowledge (whether self-limited or limited in his very being).

Genesis 50:19–20

After Jacob’s death, his sons approach Joseph out of fear that he may have been awaiting their father’s death before exacting revenge. What would he do?

Joseph insists he does not want to put himself in the place of God. Then he looks back at that brutal incident when he was so badly treated, and comments, “You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives.”

The parallelism is remarkable. Joseph does not say that his brothers maliciously sold him into slavery, and that God turned it around, after the fact, to make the story have a happy ending. How could that have been the case, if God’s intent was to bring forth the good of saving many lives?

Nor does Joseph suggest that God planned to bring him down to Egypt with first-class treatment all the way, but unfortunately the brothers mucked up his plan somewhat, resulting in the slight problem of Joseph spending a decade and a half as a slave or in prison. The story does not read that way. The brothers took certain evil initiatives, and there is no prior mention of Joseph’s travel arrangements.

As Joseph explains, God was working sovereignly in the event of his being sold into Egypt, but the brothers’ guilt is not dismissed (they intended to harm Joseph); the brothers were responsible for their action, but God was not thereby reduced to a merely contingent role; and while the brothers were evil, God himself had only good intentions.

Leviticus 20:7–8

“Consecrate yourselves and be holy, because I am the LORD your God. Keep my decrees and follow them. I am the LORD, who makes you holy.” This is only one of many passages where the command and responsibility to perform in a certain way or to be a certain thing are paired with the assurance that it is God who does the work in people.

Philippians 2:12–13

“Therefore, my dear friends, as you have always obeyed—not only in my presence, but now much more in my absence—continue to work out your salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God who works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose.”

Paul describes what the Philippians must do as obeying what he has to say, and as working out (not working for!) their own salvation. The assumption is that choice and effort are required. The “working out” of their salvation includes honestly pursuing the same attitude as that of Christ (2:5), learning to do everything the gospel demands without complaining or arguing (2:14), and much more.

Compatibilism

Most people who call themselves compatibilists are not so brash as to claim that they can tell you exactly how the two propositions fit together. All they claim is that, if terms are defined carefully enough, it is possible to show that there is no necessary contradiction between them. In other words, it is possible to outline some of the “unknowns” that are involved, and show that these “unknowns” allow for both propositions to be true.

It means when we are finished we are still going to be left with mysteries.

If compatibilism is true and if God is good, all of which the Bible affirms, then it must be the case that God stands behind good and evil in somewhat different ways; that is, he stands behind good and evil asymmetrically.

God stands behind evil in such a way that not even evil takes place outside the bounds of his sovereignty, yet the evil is not morally chargeable to him: it is always chargeable to secondary agents, to secondary causes. On the other hand, God stands behind good in such a way that it not only takes place within the bounds of his sovereignty, but it is always chargeable to him, and only derivatively to secondary agents.

If I sin, I cannot possibly do so outside the bounds of God’s sovereignty, but I alone am responsible for that sin—or perhaps I and those who tempted me, led me astray, and the like. God is not to be blamed. But if I do good, it is God working in me both to will and to act

If this sounds just a bit too convenient for God, sorry, the Bible says this is the only God there is.

Both propositions make much of human moral responsibility. The notion of freedom, in any biblical perspective, is exceedingly difficult to nail down.

It is not only in Christian thought that the notion of freedom is more difficult than at first meets the eye. Among atheists, for instance, a debate is currently taking place as to what is meant by “human freedom.”

First, human freedom cannot involve absolute power to contrary; that is, it cannot include such liberal power that God himself becomes contingent. That would deny the second of the two propositions that constitute compatibilism. That is why some of the best treatments of the will have argued that freedom (sometimes called “free agency”) should be related not to absolute power to contrary, but to voluntarism: that is, we do what we want to do, and that is why we are held accountable for what we do.

No matter how God operates behind the scenes in the crucifixion of his Son, Herod, Pontius Pilate, and the others did what they chose to do; they did what they wanted to do. That is why they are rightly held responsible. But that is quite different from saying that they had absolute power to contrary in the event, for then God himself would have been contingent, and then the cross becomes an afterthought in the mind of God.

Compatibilism is taught in the Bible, but that it is tied to the very nature of God; and on the other hand, my ignorance about many aspects of God’s nature is precisely the same ignorance that instructs me not to follow contemporary philosophers that deny that compatibilism is possible.

One of the common ingredients in most of the attempts to overthrow compatibilism is the sacrifice of mystery. The problem looks neater when, say, God is not behind evil in any sense. But quite apart from the fact that the biblical texts will not allow so easy an escape, the result is a totally non mysterious God.

And somehow the god of this picture is domesticated, completely unpuzzling.

The mystery of providence defies our attempt to tame it by reason. It is not illogical; I mean that we do not know enough to be able to unpack it and domesticate it. Perhaps we may gauge how content we are to live with our limitations by assessing whether we are comfortable in joining the biblical writers in utterances that mock our frankly idolatrous devotion to our own capacity to understand.

The Bible depicts the natural disaster’s part of it as a temporary thing that is tragic, not always easily explained, but a foretaste of judgment that is still more severe unless we actually do repent before him. For example, in Luke, chapter 13 (I mentioned Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; this is the third one), Jesus raises some questions about a recent disaster that had taken place in his own lifetime in his own country.

A tower had fallen and killed a bunch of people. He says, “What do you think? The people who died, were they worse than others? Were they more sinful than others? Did they deserve it?” So the people who are dying now in Pakistan, are they more sinful than Australians? Hmm? Long pause. He says, “No, but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.”

In other words, almost surprisingly, the God of the Bible presents these things as markers of judgment to warn us of still more severe judgment to come unless we actually do really come to him. The Bible says a lot of other things about suffering. It has a whole book just dealing with the question of innocent suffering. Job