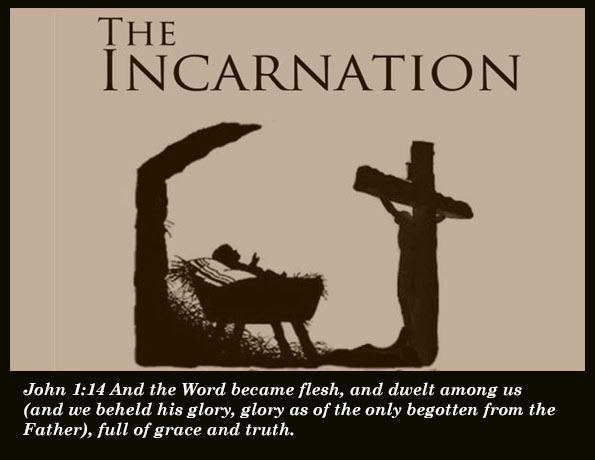

The Incarnation

[The incarnation is] “that incredible interruption, as a blow that broke the very backbone of history.… It were better to rend our robes with a great cry against blasphemy, like Caiaphas in the judgment, rather than to stand stupidly debating fine shades of pantheism in the presence of so catastrophic a claim.”—G. K. Chesterton

Micah the prophet envisages another king from the Davidic line (5:2–4). He springs from Bethlehem Ephrathah, ancestral home of David, the birthplace of his dynasty. From this village, God says, “will come for me one who will be ruler over Israel, whose origins are from of old, from ancient times” (5:2).

In the fullness of time, God arranged international affairs to ensure that Jesus was born not in Nazareth, the residence of Mary and Joseph, but in Bethlehem, their ancestral home (Luke 2). It was almost as if Almighty God was going a second mile: not only would it be said that Jesus “as to his human nature was a descendant of David” (Rom. 1:3) and thus an offshoot from Bethlehem, but that he was actually born there. Indeed, when the Magi arrived in Herod’s court to inquire as to where the promised King had been born, the chief priests and teachers of the Law quoted this passage in Micah 5 to settle the matter: he would be born in Bethlehem in Judea (Matt. 2:5–6). Though the village of Bethlehem was entirely unprepossessing (“small among the clans of Judah,” 5:2), with such a son it could “by no means” be considered “least among the rulers of Judah” (Matt. 2:6).

John 1:14 And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us (and we beheld his glory, glory as of the only begotten from the Father), full of grace and truth.

John says, “God may have been silent for 400 years, but the next word he spoke was Jesus Christ.” Nowhere is there a closer parallel to this in the New Testament than in the epistle to the Hebrews. “In the past,” Hebrews opens, “God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days, he has spoken to us in (Son).

The Son is not simply the agent of the word; the Son is the Word.

God spoke in the past to the Fathers by the prophets, but in these last days, his last word has been supremely Jesus Christ, the Word incarnate.

The Word became flesh and “tabernacled” for a while among us. He tented for a while among us. In that sense, already you have a preliminary announcement of these themes. Jesus himself is the tabernacle. Jesus himself is the temple. He’s the place where you really do meet with God.

The Holy Spirit was showing, therefore, that access to the presence of God was severely limited. It had not yet been opened up. It wasn’t disclosed. As long as the tabernacle was still standing, the tabernacle was not only the means of meeting human beings; it was also the means of emphasizing the distance. The law itself functions like that. It emphasizes what the will of God is and shows us that we can’t get there.

Not only in his incarnation, in who he is as the God-man, is he this temple where you meet with God, but, in particular, you meet with God in this temple on account of its destruction and resurrection. “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” John 2:19 The temple was the place of sacrifice. Jesus’ body is the temple, but he is himself sacrificed.

That is why in the New Testament he’s sometimes presented as the priest, the one who offers the sacrifice, sometimes as the temple where you meet with God, and sometimes as the lamb who is sacrificed. All of the various strands coming together to point to this one person, Jesus. You can think of them in several ways. The models of the Old Testament all point in one direction. He is the temple. He is the lamb who is sacrificed at the temple. He is the new priest who offers the sacrifice.

Then you can put some of them together. He is the temple, yes, the meeting place with God and man, but this temple is destroyed, and that’s why he becomes the meeting place. He must be himself sacrificed.

In particular, it is Jesus’ death and resurrection which establish him as the ultimate meeting place between God and his people. He does not simply say, “I am the true temple of God.” He says, “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it in three days.” Then the subsequent verses show he is referring to himself as the true temple of God.

Thus, in one sense his incarnation constitutes him the great meeting place between God and human beings, but in fact, in the entire drama of the gospel, the incarnation by itself is not enough. Rather, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it again.” This, then, constitutes him the great meeting place between God and his people.

Does it matter?

Is anything really lost by not believing in the Incarnation?

That God became a man in Jesus, and suffered as we do, and turned that suffering from a dead end into a creative new beginning, would be some grounds for taking the more tolerant, hopeful view.

In that sense the argument about the Incarnation matters. It matters for my faith in providence whether God became a suffering man. And it matters if he didn’t

Suppose that God did not become a man. Does that prevent us from believing that God is deeply involved in our suffering and suffers with us, and could not the suffering of Jesus still be of such a quality as to awaken in us or strengthen us in that conviction?

But need it be the only evidence, and could it taken by itself ever be sufficient evidence; and isn’t the evidence more impressive if indeed we experience on more than one occasion a hopeful creative, Godlike quality about certain people’s sufferings?

Presumably it matters to us whether Christianity is true, in which case, it could be argued, it matters if Jesus is God. If he is, then Christianity is true because it’s God’s truth. If he is not, then our grounds for believing are swept away, and we have one more opinion amongst the rest.

“By what authority do you do this?” Jesus replies, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I’ll raise it again.”

In that sense, he’s saying the authority he has to cleanse the type, to take on the type, to challenge the type, is precisely that he is the antitype, which is validated ultimately by his resurrection. Whether or not everybody understands this at the time is not the point. In fact, the next verses make it very clear they don’t.

Christianity is a profoundly historical religion. If you could somehow prove Gautama the Buddha never lived … I don’t know how you could do that, but supposing you could. If you could somehow prove Gautama the Buddha never lived, you would not destroy Buddhism, because Buddhism is a worldview which stands or falls by its internal self-consistency. It does not in any necessary way depend on the existence of Gautama himself.

There is no historical contingency in Hinduism, historical claims, no historical contingency without which Hinduism falls.

Islam, the same, all religions could have had someone else to be the revealer of that religions system, laws beliefs etc, and it would not affect their system.

Jesus was not just the revealer of God’s revelation, He was the revelation. If you take Him out of Christianity, then Christianity falls.

It is not even coherent in Christianity to ask the question, “Could God have given his revelation to someone other than Jesus?” because Jesus is the revelation.

It came through a first-century Jew, a particular man who could be seen and touched and handled and to whom witness could be borne, which is one of the reasons why in the New Testament one of the most crucial truths for getting at the essential content of the gospel is the theme of witness. I don’t know how, but somehow if you could prove Jesus never lived, you have utterly destroyed Christianity.

You know, to boldly go where no one’s ever gone before and, thus, define the truth. Despite the splint infinitive, there’s a certain kind of modernist interest in exploring the truth. Program after program in the Voyager series was really quite different. It was designed to show that all cultures are all right; it just depends on your point of view.

- C.S. Lewis calls the Incarnation “myth become fact.” Scattered generously throughout the myths of the ancient world is the strange story of a god who came down from heaven. Some tell of a god who died and rose for the life of man ( Odin, Osiris and Mesopotamian corn gods). Just as the Garden of Eden story and the Noah’s flood story appear in many different cultures, something like the Jesus story does too.

For some strange reason, many people think that this fact—that there are many mythic parallels and foreshadowings of the Christian story, points to the falsehood of the Christian story. Actually, the more witnesses tell a similar story, the more likely it is to be true. The more foreshadowings we find for an event, the more likely it is that the event will happen.

How do you, the critic who says the Incarnation is impossible, know so much that you can tell God what he can or cannot do? The skeptic should be more skeptical of himself and less skeptical of God. If the objection is that the doctrine of the Incarnation claims too much, claims to know too much, the response is that to deny it claims to know much more. (Logically, a universal negative proposition is the hardest kind to prove.)

Are all religions salvific, in the Christian sense of that term?

John Hick’s third argument relates to Christology. He wants Christians to value the metaphor of God incarnate but not suppose there actually is a divine Logos that became flesh.

Who Jesus Christ is has a controlling influence over one’s approach to the issue of Christianity and the other religions. The issue is not about morality. Christians are not automatically morally superior to other people.

The crucial issue concerns the identity of Jesus Christ. If he is just someone like us, then he may fairly be placed in the category of “good religious teachers.”

Jesus was God in the Flesh. That must be true or we have no salvation.