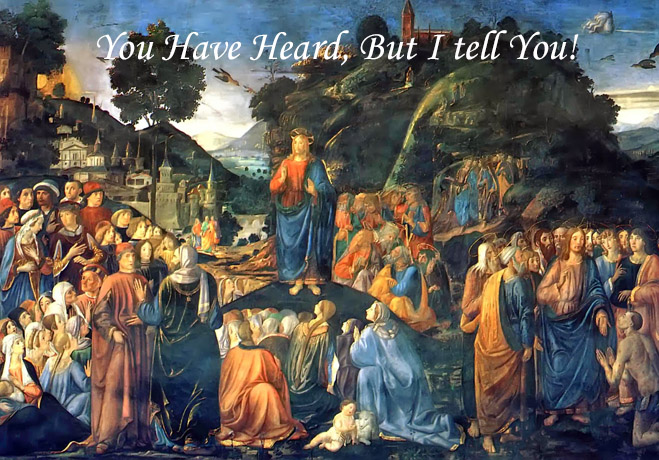

You Have Heard, But I tell You!

Matthew 5:21Ye have heard that it was said to them of old time, Thou shalt not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment: 22but I say unto you, that every one who is angry with his brother shall be in danger of the judgment; and whosoever shall say to his brother, Raca, shall be in danger of the council; and whosoever shall say, Thou fool, shall be in danger of the hell of fire. 23If therefore thou art offering thy gift at the altar, and there rememberest that thy brother hath aught against thee, 24leave there thy gift before the altar, and go thy way, first be reconciled to thy brother, and then come and offer thy gift. 25Agree with thine adversary quickly, while thou art with him in the way; lest haply the adversary deliver thee to the judge, and the judge deliver thee to the officer, and thou be cast into prison. 26Verily I say unto thee, Thou shalt by no means come out thence, till thou have paid the last farthing.

Exodus 20 Then God spoke all these words: 2 I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the place of slavery. 3 Do not have other gods besides me.

4 Do not make an idol for yourself, whether in the shape of anything in the heavens above or on the earth below or in the waters under the earth. 5 Do not bow in worship to them, and do not serve them; for I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, bringing the consequences of the fathers’ iniquity on the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate me, 7 Do not misuse the name of the LORD your God,8 Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy: 12 Honor your father and your mother so that you may have a long life in the land that the LORD your God is giving you. 13 Do not murder.14 Do not commit adultery.15 Do not steal.16 Do not give false testimony against your neighbor.

17 Do not covet your neighbor’s house.

That God is first of all concerned about what men are like on the inside is a central truth of both testaments. A good outward act is validated before God only when it honestly represents what is on the inside. “I, the Lord, search the heart, I test the mind, even to give to each man according to his ways, according to the results of his deeds” (Jeremiah 17:10).

If we understand that Jesus taught as a first-century Jew to first-century Jews, we shall expect his teaching to be framed in categories comprehensible primarily to his audience, and aimed at least in part at correcting first-century impressions and beliefs which he considered erroneous.

Jesus cannot assume that everything the people have heard concerning the content of the Old Testament Scriptures was really in the Old Testament. This is because the Pharisees and teachers of the law regarded certain oral traditions as equal in authority with the Scripture itself, thereby contaminating the teaching of Scripture with some fallacious but tenaciously held interpretations.

Therefore in each of the five blocks of the sermon, Jesus says something like this: “You have heard that it was said … but I tell you.…” He does not begin these contrasts by telling them what the Old Testament said, but what they had heard it said. This is an important observation, because Jesus is not negating something from the Old Testament, but something from their understanding of it.

Jesus appears to be concerned with two things: overthrowing erroneous traditions, and indicating authoritatively the real direction toward which the Old Testament Scriptures point.

Jesus used the phrase “You have heard that the ancients were told,” or a similar one, to introduce each of the six corrective illustrations He gives in this part of His sermon. The phrase has reference to rabbinical, traditional teaching, and in each illustration Jesus contrasts that human teaching with the divine Word of God.

Jesus implies that the ideas the ancients taught were primarily of their own devising.Jesus customarily referred to the Scriptures by such phrases as “Moses commanded,” “the prophet Isaiah said,” “it is written,” and such.

“The scribes and Pharisees of that age had completely inverted the order of things. Their carnality and self-righteousness had led them to exalt the precepts respecting ceremonial observances to the highest place and to throw the duties inculcated in the ten commandments comparatively into the background” A. Pink.

Jesus was contrasting His teaching, and the true teaching of the Old Testament Scriptures themselves, with the Jewish written and oral traditions that had accumulated over the previous several hundred years and that had so terribly perverted God’s revelation.

Martyn Lloyd-Jones pointed out, the condition of Judaism at the time of Christ was remarkably like that of the church in the early sixteenth century. The Scriptures were not translated into the languages of the people. The liturgy, the prayers, the Scripture reading, and even most of the hymns and anthems were in Latin, which none of the common people knew or understood. When a priest gave a sermon or homily, the people had nothing by which to judge what he said. They had no idea as to whether or not his message was scriptural, or even whether or not being scriptural was important. The Bible taught what the church said it taught. The church, therefore, placed its own authority over that of Scripture.

Similar to Judaism, over the centuries the Roman Catholic church had developed a system of religion that departed further and further from Scripture. It was a system that the common man had no way of investigating or verifying. The greatest contribution of the Protestant Reformation was to give the Bible to the people in their own language. It put God’s Word into the hands of God’s people. It was the truth of Scripture that brought light to the Middle Ages and consequently an end to the Dark Ages.

In a less extreme way the Jews of Jesus’ day had been separated from their Scriptures. During and after the Exile most Jews lost their use of the Hebrew language and had come to speak Aramaic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew.

The Septuagint, a Greek edition of the Old Testament, had been translated some two hundred fifty years earlier. But though it was widely used by Jews throughout the Roman Empire, the Septuagint was not used or understood by most Jews in Palestine. In addition to that, copies of the Scriptures were bulky, expensive, and far out of the financial reach of the average person. Therefore, when the Hebrew text was read and expounded in the synagogue services, most of the worshipers understood little of the text and consequently had no basis for judging the exposition. Their respect for the rabbis also led them to accept whatever those leaders said.

After the return from exile in Babylon, when Ezra and others read publicly from the law of Moses, they had to translate “to give the sense so that they [the people] understood the reading” (Neh. 8:8). Most later scribes and rabbis, however, did not attempt to translate or expound the scriptural text itself but rather taught from the Talmud, an exhaustive codification of the rabbinic traditions.

Ezra and his trained associates were using the method of Midrash upon the occasion of the completion of the Jerusalem wall in 444 BC. when they “explained the law to the people while the people remained in their place. And they read from the book, from the law of God, translating to give the sense so that they understood the reading” Nehemiah 8:7, 8

The Talmud is a body of literature in Hebrew and Aramaic, covering interpretations of legal portions of the OT, progressive establishment of traditional materials, and addition of a body of wise counsel from many rabbinical sources, spanning a time period from shortly after Ezra at about 400 BC. until approximately the AD 500s.

As the chosen custodians of God’s Word (Rom. 3:2) the Jews, above all people, should have known that God commands heart-righteousness, not just external, legalistic behavior. But because most of them had come to converse in Aramaic rather than Hebrew, the language of the Old Testament, and because the rabbis had created a vast collection of traditions, which they taught in place of the Scripture itself, the Jews of Jesus’ day were ignorant of much of the great revelation God had given them. Rabbinic interpretation of Scripture also obscured the divinely intended meaning.

As already pointed out, the traditional command you shall not commit murder was scriptural, being a rendering of Exodus 20:13. But the traditional Jewish penalty, whoever commits murder shall be liable to the court, fell short of the biblical standard in several ways. In the first place it fell short because it did not prescribe the scriptural penalty of death (Gen. 9:6; Num. 35:30–31; etc.).

MISHNA [MISH nah] (repetition) — the first, and basic, part of the TALMUD and the written basis of religious authority for traditional Judaism. The Mishna contains a written collection of traditional laws (halakoth) handed down orally from teacher to student. It was compiled across a period of about 335 years, from 200 B.C. to A.D. 135.

The Mishna is grouped into 63 treaties, or tractates, that deal with all areas of Jewish life—legal, theological, social, and religious—as taught in the schools of Palestine. Soon after the Mishna was compiled, it became known as the “iron pillar of the Torah,” since it preserves the way a Jew can follow the TORAH.

For many Jews, the Mishna ranks second only to the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures

Origin and Development of the Oral Law. The traditional Jews believe that a second law was given to Moses in addition to the first or written word, and that this second one was given orally, and handed down from generation to generation in oral form. Other scholars do not agree on this origin of the oral law and insist that it had its beginning and development after Ezra.

With cessation of the postexilic prophets and with the continual development of the complexity of life in Israel and its relationships to the outer world, there arose a need for further elaboration of the laws of the Pentateuch. Those who returned from Babylon saw this need of providing for Israel’s obedience to the law of Moses. The oral law at first was intended to be helpful so that people could obey the written word of God.

When Jesus came to speak, the Jewish leaders and the rank and file of the people were amazed at Jesus’ radical departure, in both content and delivery, from the type of teaching they were used to. Whether He was right or wrong, it was obvious to them that “He was teaching them as one having authority, and not as the scribes” (Mark 1:22).

You are not to Kill.

Man’s first crime was homicide. “It came about when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother and killed him” (Gen. 4:8). Since that day murder has been a constant part of human society.

Sociologists and psychologists report that hatred brings a person closer to murder than does any other emotion. And hatred is but an extension of anger. Anger leads to hatred, which leads to murder-in the heart if not in the act. Anger and hatred are so deadly that they can even turn to destroy the person who harbors them.

The first of six illustrations of heart-righteousness that Jesus gives in 5:21–48 deals with the sin of murder: You have heard that the ancients were told, “You shall not commit murder.”

Is murder merely an action, committed without reference to the character of the murderer? Is not something more fundamental at stake, namely, his view of other people (his victim or victims included)? Does not the murderer’s wretched anger and spiteful wrath lurk in the black shadows behind the deed itself? And does not this fact mean that the anger and wrath are themselves blameworthy?

Jesus therefore insists that not only the murderer, but anyone who is angry with his brother, will be subject to judgment.

The specific commandment to which Jesus here refers is from the Decalogue, which every Jew knew. The command “You shall not murder” (Ex. 20:13) does not prohibit every form of killing a human being. The term used has to do with criminal killing, and from many accounts and teachings in Scripture it is clear that capital punishment, just warfare, accidental homicide, and self-defense are excluded. The commandment is against the intentional killing of another human being for purely personal reasons, whatever those reasons might be.

“There are six things which the Lord hates, yes, seven which are an abomination to Him: haughty eyes, a lying tongue, and hands that shed innocent blood, a heart that devises wicked plans, feet that run rapidly to evil, a false witness who utters lies, and one who spreads strife among brothers” (Prov. 6:16–19). Murder is a despicable manifestation of a fleshly heart. The seriousness of the offense is seen in one of the last declarations in God’s Word: “Outside [of heaven] are the dogs and the sorcerers and the immoral persons and the murderers and the idolaters, and everyone who loves and practices lying” (Rev. 22:15).

Jesus attacks such self-confidence of the religious leaders, by charging that no one is truly innocent of murder, because the first step in murder is anger. The anger that lies behind murder, anger which many people think is not really a sin, is one of the worst of sins.

The Lord’s teaching about murder, whether the act is committed outwardly or not, affects our view of ourselves, our worship of God, and our relation to others.

The first effect of Jesus’ words is to shatter the illusion of self-righteousness. Like most people throughout history, the scribes and Pharisees thought that if there was any sin of which they were clearly not guilty it was murder. Whatever else they may have done, at least they had never committed murder.

According to rabbinic tradition, and to the beliefs of most cultures and religions, murder is strictly limited to the act of physically taking another person’s life. Jesus had already warned that God’s righteousness surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees v. 20

All anger is incipient murder. “Everyone who hates his brother is a murderer” (1 John 3:15)

That makes all mankind guilty, because, probably almost everyone has had that feeling at some time or another. Not only did He sweep aside all the rabbinical rubbish of tradition, but He also swept aside the self-justification that is common to all of us.

Vilifying anger and reconciliation, 5:21–26

Some early manuscripts of the New Testament add the words “without cause” after “angry with his brother”: “But I tell you that anyone who is angry with his brother without cause will be subject to judgment.”

This categorical and antithetical way of speaking is typical of much of Jesus’ preaching, and reflects, a semitic and poetic mind set.

For example, in Luke 14:26, Jesus says, “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father and mother, his wife and children, his brothers and sisters—yes, even his own life—he cannot be my disciple.” “Hate” is not to be taken absolutely. Jesus is saying rather that love and allegiance must be given in a preeminent way to himself alone; rivals must not be allowed to usurp what is not their due.

But Jesus says it in this antithetical fashion (Matt. 10:37), even though elsewhere he upholds the importance, for example, of honoring parents (Mark 7:10ff.). And indeed, it is important to let this antithetical and categorical form of statement speak, in all its stark absoluteness, before we allow it to be tempered by broader considerations. In Matthew 5:21ff., Jesus relates anger to murder: let that relationship stand before going on to observe that some anger, including anger in Jesus’ own life, is not only justifiable but good.

If anger is forbidden, so also is contempt. “Raca” is an Aramaic expression of abuse. It means “empty,” and could perhaps be translated “you blockhead!” or the like. People who indulge in actions and attitudes of this type are subject to judgment, to the Sanhedrin, to Gehenna.

Jesus is simply multiplying examples to drive the lesson home. You who think yourselves far removed, morally speaking, from murderers—have you not hated? Have you never wished someone were dead? Have you not frequently stooped to the use of contempt, even to character assassination? All such vilifying anger lies at the root of murder, and makes a thoughtful man conscious that he differs not a whit, morally speaking, from the actual murderer.

These verses make one great point. The Old Testament law forbidding murder must not be thought adequately satisfied when no blood has been shed. Rather, the law points toward a more fundamental problem, man’s vilifying anger. Jesus by his own authority insists that the judgment thought to be reserved for the actual murderer in reality hangs over the wrathful, the spiteful, the contemptuous. What man then stands uncondemned?

“But didn’t Jesus himself get very angry sometimes?”

He was certainly upset with the merchandising practiced in the temple precincts (Matt. 21:12ff. and parallels). Mark records Jesus’ anger with those who for legalistic and hypocritical reasons tried to find something wrong with the healings he performed on the Sabbath (Mark 3:1ff.). And on one occasion Jesus addressed the Pharisees and teachers of the law, “You blind fools!” (Matt. 23:17). Is Jesus guilty of serious inconsistency?

Indeed there is a place for burning with anger at sin and injustice. Our problem is that we burn with indignation and anger, not at sin and injustice, but at offense to ourselves. In none of the cases in which Jesus became angry was his personal ego wrapped up in the issue.

More telling yet, when he was unjustly arrested, unfairly tried, illegally beaten, contemptuously spit upon, crucified, mocked, when in fact he had every reason for his ego to be involved, then, as Peter says, “he did not retaliate; when he suffered, he made no threats” (1 Peter 2:23). From his parched lips came forth rather those gracious words, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34).

Let us admit it, by and large we are quick to be angry when we are personally affronted and offended, and slow to be angry when sin and injustice multiply in other areas. In these cases we are more prone to philosophize. In fact, the problem is even more complicated than that. Sometimes we get involved in a legitimate issue and discern, perhaps with accuracy, the right and the wrong of the matter.

However, in pushing the right side, our own egos get so bound up with the issue that in our view opponents are not only in the wrong but attacking us. When we react with anger, we may deceive ourselves into thinking we are defending the truth and the right, when deep down we are more concerned with defending ourselves.

In the Sermon on the Mount, despite the absolute cast in which anger is forbidden, Jesus forbids not all anger but the anger which arises out of personal relationships. This is obvious not only because of Jesus’ teaching and conduct elsewhere, and because the anger in question is that which lies at the heart of murder, but also because of the two examples which Jesus provides to give his point a cutting edge (5:23–26).

The effect on our personal lives.

It concerns the person who comes to perform his religious duty (in this case the offering of a sacrifice at the temple altar) but who has offended his brother. Jesus insists it is far more important that he be reconciled to his brother than that he discharge his religious duty; for the latter becomes pretense and sham if the worshiper has behaved so poorly that his brother has something against him.

It is more important to be cleared of offense before all men than to show up for Sunday morning worship at the regular hour. Forget the worship service and be reconciled to your brother; and only then worship God. Men love to substitute ceremony for integrity, purity, and love; but Jesus will have none of it.

The second example (5:25f.) again picks up legal metaphor. In Jesus’ day as in recent centuries, a person who defaulted in his debts could be thrown into a debtors’ prison until the amount owed was paid. Of course, while he was there he couldn’t earn anything, and therefore could scarcely be expected to pay off the debt and effect his own release; but his friends and loved ones who were eager to get him out might well put forth sustained and sacrificial efforts to provide the cash.

It would be making the metaphor run on all fours to deduce that Jesus is teaching that the heavenly court will condemn guilty people to “prison” (hell?) only until they’ve paid their debts. The debts in question are personal offenses; how then shall they be paid? And shall others pay the debt for the inmate? Rather, what Jesus is stressing is the urgency of personal reconciliation. Judgment is looming, and justice will be done: therefore keep clear of malice and offense toward others, for even the one “who is angry with his brother will be subject to judgment” (5:22). So we see that in both of these cases, it is personal animosity which is condemned.

This question is utterly urgent for all of us, but especially for those in prominent, public positions where strong viewpoints are expressed as part of one’s calling—positions like President of the United States, or Speaker of the House, or Governor of Georgia, or network news commentator or host of a radio show like Focus on the Family or preacher in a local church.

In every one of these roles, the moment one opens his mouth someone disagrees. And if the issue is hot enough, that disagreement can be felt as anger and alienation. At any given moment, for example, the President of the United States has millions of people calling him a hero and millions calling him a jerk. That was true of Abraham Lincoln and it will be true of every president that ever serves. And it is true of every other public role. So, are all these people responsible, before they worship, to contact every person who has something against them? That would be impossible, it seems.

But it’s not our inability to see how it would work that raises the question. It’s the context. Go back 14 verses to verse 9. There Jesus says, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.” Yes, and that is what this text is about too. Be a peacemaker before you worship. Be reconciled with those who have something against you, before you bring your Freeing the Future pledge next Sunday.

Listen to what comes next in Matthew 5:10–12:

What Jesus says is that sometimes people will hold something against you when they shouldn’t—insulting you, persecuting you, saying all kinds of evil against you falsely. What do you do in such circumstances? Do you stop worshiping as long as someone feels like this about you?

If so, Jesus would never have been able to worship in the latter years of his life. He was constantly opposed. They sought to trip him up in his speech. They tried to kill him. They tried to shame him. Was he responsible for this? Not only that, he said that the same would be true for his disciples. In Matthew 24:9 he said, “You will be hated by all nations on account of my name.” In other words, “If you are faithful to me, somebody will always have something against you.

We are only responsible for what others hold against us when it is owing to real sin or blundering on our part.

We are responsible to pursue reconciliation, but live with the pain if it does not succeed. In other words, we are not responsible to make reconciliation happen.

Paul says in Romans 12:18, “If possible, so far as it depends on you, be at peace with all men.” So far as it depends on you. Jesus took every step required of a human being to make matters right with his enemies (he never sinned), and still they had things against him and were not reconciled to him.